The No-Win Dynamic: Understanding Antisemitism and Israel

Edginess, Outrage, and a New Generation of Antisemitism

Today, we’re sharing a conversation Sarah and Beth had last week with Yair Rosenberg. Yair Rosenberg writes about the intersection of politics, culture, and religion for The Atlantic. You may remember his name because he has been on Pantsuit Politics twice before. We keep inviting him back because he has a gift for “unpacking and explaining” what’s going on, particularly in Israel, without lecturing1.

Last Fall, Sarah wrote about the jarring experience of encountering antisemitism in her community, and then, as though he had been reading her mind, Yair wrote about the phenomenon, and we wanted to have him on to talk about the growing generational divide in antisemitic attitudes in the US.

In today’s interview, Yair said several things that stood out to me. Before I get too far in sharing my notes, I want to note that he warned us against the dangers of comparison (especially where it relates to the holocaust):

“Once you invoke the holocaust, whether in an earnest way or an edgy way, the debate quickly becomes about the analogy rather than the conduct you were trying to discuss or condemn.”

So, I want to acknowledge that I’m breaking his rule, and compare this conversation to MLK Day.

Yesterday was the Martin Luther King, Jr. Holiday, and just ask a member of the King Family how frustrating it is to see people quote Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech once a year and then not do anything for the other 364 days of the year to make his dream a reality (or worse, systematically dismantle the progress we have made towards racial equality in our country).

Today, I appreciate the call to think about prejudice for a second day in a row, and the gnarly, sneaky ways it creeps into our culture from so many fronts. If you want to, there are a lot of people to hate.

In the second part of the interview, Yair helps us unpack and explain the politics on the ground in Israel right now. Not as a proxy for the US or evil empire, but as a struggling democracy where a strong-man style leader has made a bargain with the most extreme right-wing factions in his country to consolidate power and institute hugely unpopular policies in an important election year (#relateable).

Today’s episode isn’t asking you to change your mind about Palestinian liberation, Israel, Gaza, settlements, war, protest, or what US policy should be in Southwest Asia. I think there is an invitation in today’s episode to do what we do here at Pantsuit Politics: look a layer or two beneath the headlines and let the complexity work on us. As always, we look forward to hearing your thoughts. -Maggie

Topics Discussed

The Generational Shift in Antisemitism

Israeli Politics for Real

Outside of Politics: Middle and Maiden Names

Want more Pantsuit Politics? Subscribe to ensure you never miss an episode and get access to our premium shows and community.

Episode Resources

Pantsuit Politics Resources

Save the Date: Spice Conference and Live Show in Minneapolis! August 28 and 29, 2026

Yair Rosenberg on Pantsuit Politics

Understanding the Generational Divide of Antisemitism

‘The More I’m Around Young People, the More Panicked I Am’ (Yair Rosenberg | The Atlantic)

There’s Something Missing in Films About Jewish Cultural Figures (The New York Times)

Never Pure: Historical Studies of Science as if It Was Produced by People with Bodies, Situated in Time, Space, Culture, and Society, and Struggling for Credibility and Authority by Stephen Shapin

The State of Politics and Elections in Israel

Why Israel Might Have Argued Against an Iran Strike (Commentary Magazine)

Israel Watches Iran Protests Closely, but Is Wary of Intervening (The New York Times)

Thousands rally in Jerusalem to demand ultra-Orthodox IDF enlistment (The Times of Israel)

How Changes in the Israeli Military Led to the Failure of October 7 (New Lines Magazine)

Abbas says Ra’am party will be open to Jewish candidates, in major shift (The Times of Israel)

‘The Sea’ Wins Best Film In Somber Israeli Ophir Awards Dominated By Gaza (Deadline)

Israeli Film Academy Awards Face Government Defunding After Anti-War Movie ‘The Sea’ Wins Top Prize (Variety)

Netanyahu alleges Israeli election fraud, accuses rival of duplicity (Reuters)

Episode Transcript

Sarah [00:00:13] This is Sarah Stewart Holland.

Beth [00:00:15] This is Beth Silvers.

Sarah [00:00:16] You’re listening to Pantsuit Politics. Over the last several years, the world has seen a decided acceleration in antisemitism. We’ve talked about that many times here in many ways. We’re both seeing an increased normalization of these attitudes in our own communities and wanted to come back to it again. We’ve brought back one of our favorite reoccurring guests, Yair Rosenberg from the Atlantic, to help us talk about what is causing the normalization of this very specific kind of hate. And we’re going to take a real hard turn and Outside of Politics and talk about our middle names.

Beth [00:00:50] Before we dive into all of that, we have very exciting news to share. We are thrilled to announce that we are finally coming to Minneapolis. We have wanted to visit the Twin Cities for years. This August, we’re making it happen in a big way, and we’re so glad to be able to do that. We’re so good to have something really positive and uplifting to describe, as we’re talking about Minneapolis so often on the show these days. On Saturday, August 29th, we will be doing a live show at the Hyatt Centric, followed by an after party. Now, if you’ve been to one of our live shows before, you know that this is a joyous, high energy, thoughtful, fun experience, emphasis on fun.

Sarah [00:01:31] We’re funny. I just want to say that. Like we’re really funny live. I don’t mind tooting our own horn.

Beth [00:01:38] I know people come not sure what to expect from a news and politics podcast on stage. We have a good time and you will have a time with us. I’m just telling you. And here is what we are also very excited about. And we are launching, in connection with this live show, our first ever Spice Conference.

Sarah [00:02:01] This will be a weekend experience for premium members, kicking off Friday night, August 28th with a welcome party. On Saturday before the live show, we’ll have engaging sessions, fun activities, chances to connect with listeners from Minnesota and around the country. And for our executive producers, we’re offering a special retreat starting Thursday, August 27th. A full extra day of activities before the Spice Conference and live show. So here’s what you need to know about getting tickets. EP Retreat registration is officially open and sales for that begin on February 2nd. For the Spice Conference, we’re doing something different to make it fair for everyone across time zones. We’re releasing tickets in two batches, the first on Tuesday, February 10th at 9 p.m. Eastern and the second on Wednesday, February 11th at noon Eastern. So mark your calendars for one of those times because we know these tickets will go fast.

Beth [00:02:49] If you just want to come to the Saturday Night Live Show, stay tuned, those tickets will go on sale in early March. So I know it feels a little complicated. There’s a lot going on, but the headline is come hang out with us in Minneapolis. We’re so excited. You can find all the details at pantsuitpoliticshow.com. We cannot wait to see you there.

Sarah [00:03:06] Up next, Yair Rosenberg from the Atlantic. Yair, welcome back to Pantsuit Politics.

Yair Rosenberg [00:03:20] It’s always good to be here.

Sarah [00:03:22] Let me tell you why you’re one of my favorite people to have on the show. Because you can have a journalist on that covers Israel but doesn’t feel comfortable speaking to anti-Semitism. And there are antisemitism experts who say they’re not knowledgeable in Israeli politics. And I find that a very unhelpful dynamic and you don’t do that because you talk well and expertly about both. And that’s why I love having you on the show.

Yair Rosenberg [00:03:45] Yeah. I don’t feel like you can talk about those things unless you’re able to address that intermix.

Sarah [00:03:52] Exactly. That is exactly what I want to talk to you about. I know that you’ve been doing a lot of writing about the generational crisis with regards to anti-Semitism. And I have been thinking a lot about this too particularly in this relationship to Israel, because it feels like to me you have this crisis, this way both sides feed this beast of antisemitism on the right support for Israel seems to like be fueling the antisemitism and the conspiracies and Candice Owens. And then on the left criticism of Israel also seems to be feeding a certain type, facet of antisemitism. And as I was thinking about this and I really wanted to talk to you about this. Looking back, 44, particularly of my time in D.C. And the aughts and the 90s, it felt like those things were related because the answer implicitly and sometimes explicitly to anti-Semitism was support for Israel. That was the ethical argument, right? And so as this has crumbled, I find myself being like, well, support feeds it, criticism feeds it, politicians are still stuck that this is the answer and it just feels like I’m rest.

Yair Rosenberg [00:05:14] Yeah, well I think you’re pointing to something that you see a lot when you cover and pay attention to antisemitism, which is this no-win dynamic, which is how prejudice works. Prejudice comes from pre-judging. You already know where you want to go. You already have your opinion, let’s say, about Jews. And then you can take any line of argument or criticism or particular fact pattern and then use it to justify the thing you wanted to get to in the place. An example I give of this well outside the antisemitism conversation was during the 2008 election campaign. I was talking to a cousin of mine. And this cousin didn’t really follow politics. He was studying Jewish religious texts in Yeshiva. But he said to me, I know you know this stuff. I have a question. I’ve been hearing all these things about how we should be worried about this Barack Obama guy because people have been saying he’s a secret Muslim. But then I also heard people say to me that I should worry about him because he has this anti-American pastor in his church, this guy named Jeremiah Wright, if people remember that controversy.

Sarah [00:06:19] I do.

Yair Rosenberg [00:06:19] So this guy did not know very much about politics, but he knew a lot of Talmud and he could spot a contradiction when he saw one. And he said, “If he’s a secret Muslim, why am I worried about his Christian pastor?” And if this Christian pastor is the problem, then how could he be a secret Muslim?” And so when I said to him, that’s because people here are the certain people who are just very, very opposed to this person, sometimes for prejudicial reasons. And so they can make any argument go in that direction, whichever way, and it doesn’t have to go here. And that’s, as you said, you can be a critic of Israel and find a way to use, you to say that here’s my criticism of Israel. And some people will take that and use that into justification for attacking Jews. And then you could a supporter in a community that’s supportive of Israel, and other people will take that and turn that into a justification for saying, well, the Jews must run everything, therefore, we must go after the Jews. It’s this no-win situation heads the antisemites win, tales the Jews lose. One of the valuable things we can do in journalism and when just average people thinking about prejudice, which includes antisemitism, is to look for those contradictions. I think sometimes our conversation is like let’s label and lecture about something rather than try to unpack it and explain to people those contradicting because when you can expose those, it makes it easier for people not to fall for them and to have a more thoughtful conversation. So that’s what I try to do.

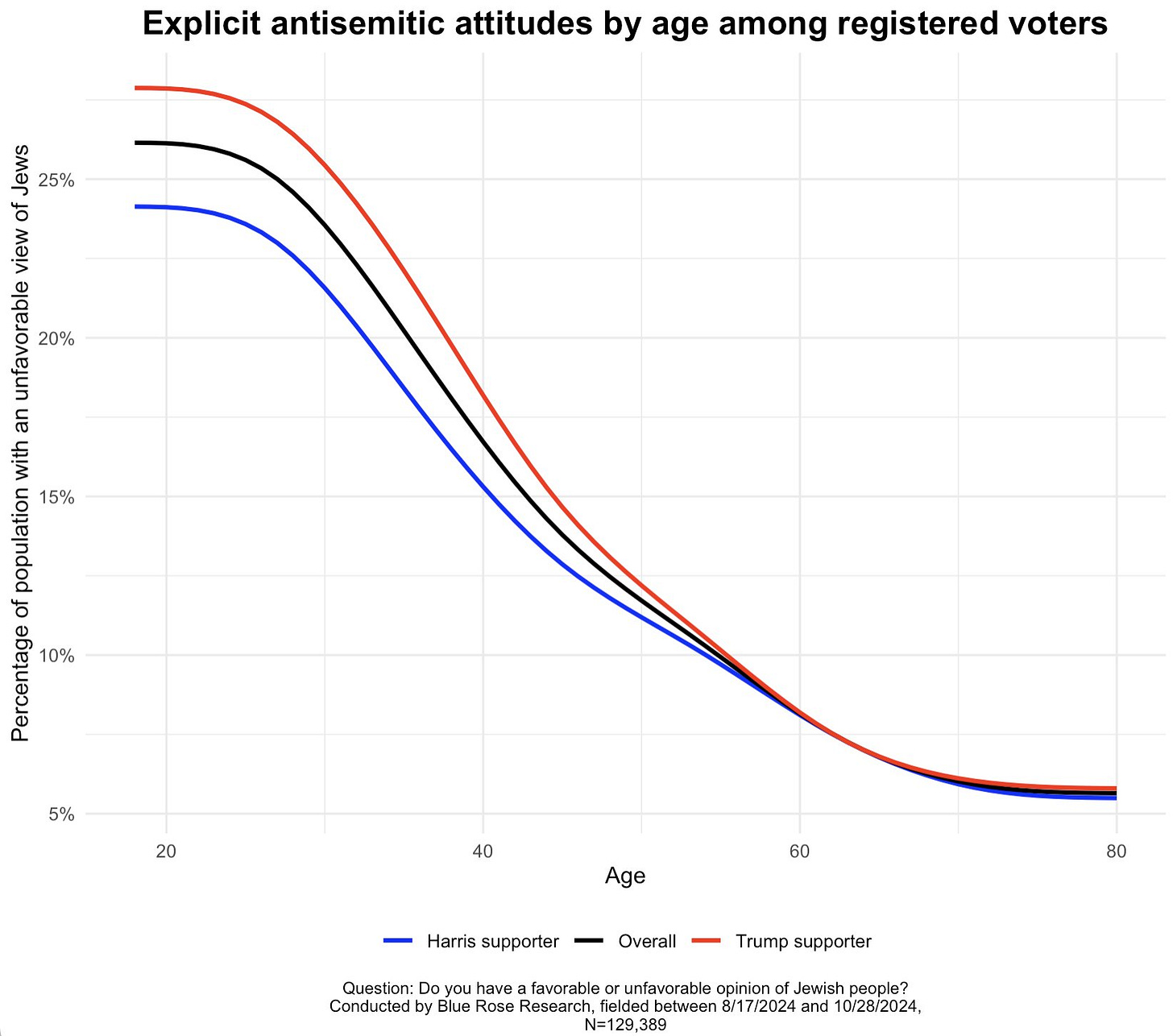

Beth [00:07:36] You talk in your recent writing about this generational issue and how more than partisanship age is telling us a lot about where antisemitism is flourishing. Why do you think it is that young people are more comfortable-- I really have parked mentally on the words warm and cooling in your writing. It’s interesting to me to think about prejudice in terms of like how warm are we towards a particular group of people or how chilled are we? So I wonder if you could talk about why you think young people are so comfortable, not in a majority sense, but in a growing sense, expressing antisemitism.

Yair Rosenberg [00:08:16] So my article about this went through a tremendous number of studies that tried to understand anti-Semitic sentiments and who agrees with them. What I pointed out is that these studies all have their unique facets and they don’t all agree entirely, but they had this one thing they all agreed on, which is that the younger a person was the more likely they were to express some form of antisemitic views. And as you said, that’s not the majority of young people. It’s still a minority of young people, but many more young people were likely to say something or agree with something antisemitic than older people. One very arresting example of this was polling done by David Schor, who did polling for the Kamala Harris campaign. And when you poll for presidential campaigns, they want to understand the electorate they’re trying to reach with their ads, and they have tremendous, insane numbers of resources, hundreds of millions of dollars. You could do things that normal pollsters can’t. And in this case, that meant that David Schorr could poll over 100,000 people on a large number of things. And one of them was do you have a favorable or unfavorable opinion of Jewish people? Note he asked about Jewish people, not Israel, not Zionism. And he found that young people under 25-30, 25% of them were likely to say that they said that they had an unfavorable opinion of Jewish people, but the older you got the more that just completely fell off the map. People just were not going to say that and did not have unfavorably opinions. And so you have a lot of this data showing this. And then the question is why? And you could write an entire book about it. We could be here all day. It’s it’s really, really a whole bunch of things. It is never just one thing. One of the obvious ones is the fading memory of World War II and the Holocaust but not in the sense that I think most people think about it.

[00:09:54] People think, oh, we’ve forgotten the Holocaust because the survivors of the Holocaust, the Jews who survived the Holocaust are fading away and who’s here to tell their stories so people remember what antisemitism does and how it destroys societies and people. But actually, the thing that changed American attitudes on antisemitism wasn’t Holocaust survivors telling their stories, it was Americans experiencing the predations and horrors of Nazi Germany, mainly when they went over to fight in World War II. We drafted men from all over the country, all over North America, and they went and fought in Europe. They defeated the Nazis, and then they ended up liberating death camps where they found just two out of every three European Jews had been killed. These horrific scenes that these people write about, these American soldiers write about back home. I wrote about how you have these letters where someone says, I was eager to go and liberate one of these death camps because that way I would see for myself what had actually happened because I was sure that what they said about it had been exaggerated. It couldn’t possibly have been that bad. And so now I would see for myself and I didn’t have to worry as much. And then, of course, it turned out it was much worse than I’d been told. And so when the allies liberate these camps, President Eisenhower goes himself personally to visit. He brings members of Congress and journalists to see what happened because he says people one day might deny this. And this comes back to America in the form of all these soldiers who tell their communities, who write about it in their papers, tell their church groups. And that generation, and then the generation after them, who were curious about it firsthand, their attitudes about Jews are profoundly changed.

[00:11:25] And what I mean by that is most people don’t know this because we don’t remember it. But before the United States entered World War II, attitudes towards Jewish people were not great. In fact, Americans were extremely suspicious of Jews. They did not want to let Jewish refugees into America. They repeatedly told pollsters that they were opposed to it. They didn’t want to let Jewish child refugees into America. They told pollsters they were worried that Jews might be German spies, and that’s something that was actually echoed by none other than Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who said Jews might be spying because they’re under duress from the Nazis. They might have their families and things like that. In reality, that sort of thing was vanishingly rare, but this was a real sentiment. It’s why America did not raise immigration quotas for Jews trying to flee the Nazis. It’s why American didn’t bomb Auschwitz or the railway tracks to Auschwitz. There was this general climate of suspicion and hostility towards Jewish people. I mean, the poll that I like to cite is the Gallup, which does presidential polling for us to this day and many other kinds of polling. On the eve of Kristallnacht and the Nuremberg laws, polled Americans and said, “Is the persecution of Jews in Europe a very paltry entirely their fault, partly their fault, not much their fault, or not at all their fault?” So they’re saying, is it the Jews’ fault that they’re being persecuted in Europe?

Sarah [00:12:41] Oh my goodness.

Beth [00:12:42] The majority of Americans said it was either somewhat their fault or all their fault. That’s on the eve of the Holocaust. So you can see why America didn’t have an interest really intervening on behalf of the Jews in this conflict. But then of course Pearl Harbor happens and America joins the war for its own national security reasons. And then along the way, they end up liberating these death camps and that changes everything. These people come back home they tell their stories. And then suddenly the American myth changes. The American myth becomes America correctly was the people who defeated the Nazis, who ended the Holocaust. And thus to be antisemitic was in some way to be Anti-American. And that holds for a generation or two. But just the nature of things-- there’s nothing nefarious about it-- is that as time goes on, generations pass on and then new generations arise. And the youngest generation of Americans has absolutely no conception of this and didn’t experience this. And so they’re returning to the American baseline of suspicion and sometimes hostility towards Jewish people. And that makes them more susceptible to antisemitism. So that’s one example why young people would very naturally be less immune to antisemitic ideas. Another example, of course, would be that young people are much more likely to get their news and information on social media. And this is not news to anybody. And there are very good reasons why people would get their news on social media. My profession has made its share of mistakes and has lost trust in audiences in various ways, hasn’t learned necessarily always how to use new technologies to reach new readers. I always say I think that people should have a balanced diet of information. They shouldn’t just be reading me and the Atlantic. They should also be getting their news on social media and figuring out how to get the best stuff in from the best places. But the surveys that we have show that if you’re the older you are, the more likely you’re getting your news from traditional media. The younger you are, you’re more likely to get it from social media platforms. And one of the disadvantages of social media platforms is that they advantage certain kinds of fabrications and conspiracies and don’t have any sort of editorial standards or ways to stop that.

[00:14:29] So to just give some obvious examples, if you think about how social media works, it’s a lot of people talking all at the same time, trying to gain attention, often talking about the same things and the same issues of the day. So the way you can stand out from that cacophony and say go viral and succeed is you have to have something that other people don’t have. So you could have a cuter cat than everybody else. You could be funnier than everybody else. You could be more inflammatory than everybody else and that’s where we get to some of the negative consequences because that will stand out. After Charlie Kirk is shot, 99.9% of people are saying that’s horrible, and I’m thinking of his family, but 0.1% of people are saying, glad, let’s see more of it. Those people will get all the attention, lots of it negative, but they will break through because they are distinct and inflammatory, and they’re novel. So you have this thing other people don’t have. One way that journalists would do this, of course, is to have information that other people don’t have, to be able to explain something that just happened that other people can’t explain. So if there’s some catastrophe in the world, I don’t know, a bridge falls down, a war starts, you can explain that to people and that can be valuable and that’s what journalists do. But the thing is that takes time and effort and it takes a lot of work and it’s not always so fast. But what is very fast is if you just make it up. And that’s where you get social media incentivizing fabrication because when things are happening and you want to stand out, you can make stuff up about them and in particular you can make up conspiratorial explanations for world events.

[00:15:51] And antisemitism as we discussed on this podcast, is not just a personal prejudice where you don’t like people who are different whether they’re too Muslim too Jewish too black. It’s also a conspiracy theory about how the world works. It says that sinister, string-pulling Jews are behind the world’s social, political, and economic problems. So if we turn over our communication infrastructure, especially for the younger generation, two ways of talking that privilege fabrication and conspiracy theories, you should expect there to be more antisemitic conspiracy theories in our public discourse, particularly among people who use those platforms. A couple other things I would raise, one is the rise of populist politics in America. Since 2016, we’ve seen revolts against elites in both political parties. Donald Trump’s hostile takeover that was successful in the Republican Party. Bernie Sanders’ nearly successful campaign in 2016 as well, in the Democratic Party, which didn’t win, but profoundly changed democratic politics. What these populist movements share is, in my view, a partly justified critique of the management of American society by its elites, economic, academic, journalistic, saying we’ve gotten to all these wars. Our economy isn’t serving us the way we thought it would. All of these other issues that people have with how elite actors have managed their society. Populists come along and say, these people failed and we need to throw them out. We need to replace them. Populism has a long history in American politics and it can be very good as a corrective for problems in a society. But the thing about the populist narrative is it says that there’s this group of elites that is messing over the masses. That’s the fundamental narrative. And that’s just a hop, skip, and a jump away from there’s a Jewish belief that’s messing over the masses. It basically rhymes. So the more populism you have in your politics, the more antisemitism you should expect. And so it goes on and on, and we haven’t even touched Israel. That’s the next slide.

Sarah [00:17:42] Well, and that’s the thing. That’s what I was thinking about as you were talking about this. I think about the policy towards Israel a lot and how it affects us. I think, about, obviously, World War II. And I think, for me, growing up-- again, I’m an elder millennial. I was born in 1981. And there’s, like, such a cultural component, too. I think all the time about that Atlantic piece, the Jewish century. I thought it was so good because it really touched on the 20th century and this incredible moment of both incredible influence of particularly immigrants, Jewish immigrants coming post-World War II and incredible influence and rising up the ranks of American society. But also that influence was flowing both ways and it was not complete assimilation, but there was this mutual back and forth between the culture in ways that I think really impacted me. I wasn’t listening to World War II soldiers. I was too young, but I sure as hell was watching Schindler’s List. I was seeing all this cultural messaging and language. And I’ve been thinking about this because there’s a great piece in the New York Times magazine about Song Sung Blue and Neil Diamond and how the Jewishness and the Jewish identity of Neil Diamond was erased from this movie and erased more and more culturally. Like you will have a character that you know to be Jewish, but the influence of Judaism and the Jewish identity is sort of fading. And I think about how in this very special moment of time, both were present. There was an influence on American culture and assimilation and there was this other back and forth paradoxically that I think was a key component as well of tamping down that conspiracy. It’s the opposite of populism. It’s pluralism. And I don’t know where we lost that or why it’s fading. I mean, in some ways it makes sense with me for the young. Yeah, pluralism, you have to grow up. You have to meet people different from you. You have experiences culturally, societally, relationships, that teach you like my reductive understanding of the world at 21 was not true. So part of that is intuitive, but I do see something very different culturally that I think is wrapped up in our politics because so much of our politics has become so much of our culture.

Yair Rosenberg [00:20:04] There’s a lot of things in there.

Sarah [00:20:06] That’s the question. I just need to work that out with you Yair.

Yair Rosenberg [00:20:08] No, but that’s right. I do think the part about how our politics and our culture are intertwined, I was on one show, a very different show, more conservative show where they were asking me about this stuff and they were saying the Jews that people hear about today are not that it used to be. You had these Jewish intellectual or other heroes like I don’t know Albert Einstein and who are those people today? And I said to the to the host. It’s a fair point. Who are the models that you’d hold up of sort of people? Who are Jewish that people identify with and can learn from in that way? But I said, who exactly does anybody agree about in that way? We are so polarized politically and culturally that it’s very hard to find-- even Taylor Swift becomes divisive.

Sarah [00:20:52] Dolly Parton. I got one.

Yair Rosenberg [00:20:54] Yeah, I think that’s something very telling, right? Which is that you have to be of a previous generation of a previous age. You have to think of grandfather [crosstalk]. But after a certain point nobody can actually be that uniform thing. So you couldn’t have. Imagine for example in the past it would be like I don’t know Jonas Salk, who comes up with all these medical innovations and vaccinations stuff like that on curing diseases. But you know what, the Jewish CEO of Pfizer or whatever is a villain for a significant number of people because turns out making a vaccine and curing a massive worldwide pandemic is actually not something that unites everybody anymore. Now we have a lot of divisions over that, which is downstream in a way from our politics and relates to our culture. And so it’s very, very hard. And I think this isn’t just true for Jews for sort of like models and positive visions from minority communities to gain widespread purchase because nothing can. That makes it harder for people to just get along and to find things they like about each other, which is of course very disquieting.

Beth [00:21:58] How do you think about this trend line with young people and antisemitism existing in the landscape of an anti-woke backlash?

Yair Rosenberg [00:22:09] Yeah, so one element right-wing antisemitism today is the anti-woke backlash resulted in people being deliberately more transgressive to show that we’re not going to put up with this political correctness with these impositions that we consider to be unfair on our speech and our conduct. And again, some of these critiques were valid. But taken to an extreme, it basically becomes what’s the most sacred cow we can slaughter as a way of showing how transgressively we are? And that results in proliferations of Hitler jokes and edgy antisemitic jokes. And for many people they are jokes, but then for other people they’re not. And when so many people are making them it becomes hard to distinguish a punchline from a punch.

Sarah [00:22:50] And his best friend’s misogyny. Lots of that going around, too. Women shouldn’t vote. Like all manner of bullshit.

Yair Rosenberg [00:22:58] All that kind of stuff is basically like what is society’s sacred cow? Okay, feminism, antisemitism, these kinds of things, let’s purposely transgress. And then again you have some people for whom this is an edgy performance art that they will hopefully grow out of. And other people for whom this is a sincere thing. A Nick Fuentes type character. And then people who straddle the line one way or the other. Increasingly, part of our culture is filled up with this kind of performance. And a certain amount of energy then gets devoted to figure out who is who and whether we should be worried and to what extent? And so I think you’re right to point to the anti-woke element of this.

Beth [00:23:34] And I don’t know how to get out of this cycle when on the other side of the political aisle, especially right now, there are so many Holocaust World War II references to try to come up with some analogy for the way that people are worried about our government’s creeping authoritarianism. So it just feels to me like this feeding frenzy back and forth where it’s not really sacred to anyone because we’re all just employing it for our own projects, some of us with better intentions than others, but I just feel trapped in this doom loop of edginess and outrage.

Yair Rosenberg [00:24:16] I try myself to not rely too much on Holocaust analogies one way or the other for this reason. I feel that they largely don’t serve a productive role. Regardless of whether or not I might agree with them. Because there are absolutely certain cases, example I’ve written about the Uighur genocide in China, where I feel like there’s horrific parallels. But the thing is once you invoke the Holocaust, whether in an earnest way or an edgy way, the debate quickly becomes about the analogy rather than the conduct you were trying to discuss or condemn. And so that’s one of the reasons why I just completely avoid this despite being someone who writes all the time about Jewish issues, Jewish affairs, and antisemitism. I seldom invoke this in that way. And I think that abstaining, the only way to win this game is not to play. And to say when we talk about the Holocaust, we talk about it specifically and as a historical event and certain things like that. The further out one makes Holocaust analogies, the less likely they are to do what you think you want them to do. And so it actually is paradoxically unhelpful to a cause to invoke it. And so that to me is why it’s similar to what I said with like antisemitism; you want to unpack it, you want to unpack contradictions, you want to explain it, you want it to be calmly walking people through why something might be a problem or prejudicial. What you don’t want to do is just say antisemitism and label and lecture right at the top. It’s not effective. And similarly, if something’s really horrible in the world and you want to raise alarm about it, you don’t want to say holocaust at the top. You want to walk people through it and you want to do so calmly and carefully and with compassion. And then you find you probably don’t need that punchline in the first place. But only if you’ve earned it, should you invoke it. And I think sometimes especially social media and character limits encourages people to jump to the most extreme characterization.

Sarah [00:26:00] Yeah, we want to earn it by invoking it.

Yair Rosenberg [00:26:03] Exactly.

Sarah [00:26:05] I mean, and I feel like a little bit that this is what happens with Israel. I just feel like the word comes out of your mouth and we’re not talking about the country. We’re not taking about the people. We’re not talking about leadership. It’s just becomes this caricature or mythology. I don’t even know the word I want. It makes everything so cloudy. And I think you’re really good at saying, okay, can we actually talk about what’s happening in Israel? Can we actually talk about the country? Because I know this is a big year. I know with the trial, I know there could be an election and with this sort of ceasefire, which feels like maybe not the best word for it. So what are you seeing with regards to the actual country, not the word invoked to obfuscate what other people actually want to talk about.

Yair Rosenberg [00:26:57] A teacher of mine, Stephen Shapin, who’s a professor at Harvard, wrote a book once. He’s a historian of science, and he says, it was like something like, a history of science as if it was performed by real people living in real social and historical contexts, struggling for trust and relevance in real world situations, which of course how science actually happens but isn’t always discussed. Similarly, talking about Israel as if was a real country with real people with real different dynamics and opposing parties, and differences of opinions and complicatedness messiness and brokenness. That is the way all countries ought to be discussed, but certain countries like Israel often occupy a sort of symbolic role in people’s imaginations, whether positive or negative, which makes it very hard to actually see with the real country. And so, yeah, what’s going on in Israel? So many different things. One is that the whole country is on alert right now because if President Trump decides to intervene and strike Iran, it’s entirely possible the Iranians will strike Israel in response, rather than the U.S., which is much harder to get at, even on its bases. And then Israel would have to decide what to do. You have, as you said, an election that legally has to happen this year at latest by October. But it could happen earlier if the Netanyahu government falls apart on its own contradictions. And it has a bunch of those. Chief among them, there’s a huge controversy in Israel over drafting Ultra-Orthodox Jews into the Israeli army. For those who are not familiar, Israel does not have a volunteer army like we do. They have a mandatory conscription army. But there are some groups that have exceptions. One of them is Arab citizens of Israel. They don’t have to serve if they don’t want to. Some do, and many don’t. And another is Ultra-Orthodox Jews who for various historical and religious reasons got a carve out that said you can basically study religious texts and not serve in the army. And that worked when they were a very small part of the population. But today, because they have very high birth rates, they’re one of the highest, fastest growing populations in Israel. And Israel feels that it needs all the manpower it can get. October 7th happened in part because they decided we’re going to rely on sort of an electronic fence and high tech measures to watch our border instead of just people. And it turned out that was a big mistake.

[00:28:59] And so you end up with all of these conflicts and with all these errors, people saying we desperately need more manpower and we have this huge portion of the population that’s only growing that refuses to serve in a mandatory conscription army. And people find that extraordinarily unfair as their whole lives go on hold, as their sons and daughters go out and die and get injured. And so this is a huge controversy in Israel. And Netanyahu’s government is on the wrong side of it, which is to say that upwards of 70% of Israelis think that the Ultra-Orthodox should be drafted. Netanyahu’s government though relies in large part on those Ultra-orthodox political parties to stay in power. And so he has to continue the exemption to keep his government together. But even the people who voted for his own party, even members of his own part, they’ve turned on this point. And so you have the coalition at loggerheads with itself over this issue. And if they can’t come up with something that solves it, especially since Israel’s Supreme Court has demanded that they fix it because they say it’s basically inequality to draft some people but not others without a very good reason. The government might just not be able to pass a budget, not be to pass laws, and eventually fall apart, have a no-confidence vote, and then you end up with even earlier elections. And if those happen, well, it might be a shock to people outside Israel, but polls have been showing since before October 7th that the current Israeli government is extremely unpopular and would lose. It certainly would get many, many fewer seats in parliament than it has now. The only real question is how many seats all the other opposition parties would get.

[00:30:24] And there’s going to be a real scramble to try to oust Netanyahu in a more decisive way than the last time it happened, where it was just barely cobbled together and a coalition lasted for one year. It looks like there’s a more solid group of opposition parties that can do this. If we want to get into the real nitty-gritty, Israel has 120 seats in the parliament in the Knesset. You need 61 of those seats to have a coalition and then the head of the biggest party or the most or sometimes just a one of the more important parties is the Prime Minister and the opposition coalition is basically pulling around 59/60 seats right now. And then the Netanyahu’s coalition is pulling around like 50 seats. Who are the other 10 seats that are that are missing math here? Those are the Arab parties in Israel’s Parliament. And some of them are very unlikely to serve in an Israeli coalition, but one of them, the largest one, religious Islamist party named Ram actually served in the last anti-Netanyahu government and is willing to do so again. So the question is how many seats do the opposition parties get without that Arab Party? And then would that Arab Party join which would give them even more seats? Would the Arab Party support a coalition but not join because you can vote with the coalition, but not be in the coalition? These are all the things we don’t have to think about in American politics.

Sarah [00:31:43] I was actually thinking some of this sounds familiar with independence in Maine and who are they going to caucus with and like we’re so close and we’re fighting over this little sliver in the middle.

Yair Rosenberg [00:31:52] Yeah, so if you’re in certain state-level politics in America, it actually does make sense. Whereas, in our national politics, it doesn’t really because we force everybody into Republicans and Democrats.

Sarah [00:32:00] True.

Yair Rosenberg [00:32:00] Although, in practice, you have the factions, even so, they’re just within the parties. You have Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and more progressive Democrats, and then you have Thomas Massie and Marjorie Taylor Greene and people like that who are a small but real protest faction within the Trump Republican Party. So imagine those were all distinct parties and then they all have to get together and come up with a coalition and then choose who gets to be president. That’s basically what the Israelis are doing. And the opposition coalition, Israel, has outpolled Netanyahu’s since before October 7th because he’s on the wrong side of a whole lot of issues. He’s on the wrong side of the Ultra-Orthodox conscription issue. He’s seen as the person who fundamentally failed to secure Israel, which is why October 7th happened. He’s tried to escape responsibility by blaming it on literally everybody but himself. It hasn’t really worked. We had, I think, an episode on this at some point. He tried to overhaul Israel’s Supreme Court and Judiciary and subordinated to the politicians. And that was also a 70-30 issue that he was on the wrong side of. So you add up enough 70- 30 issues where you’re on the wrong side, but you do them because you have either Ultra-Orthodox partners or settler right wing partners who demand certain things that most Israelis don’t actually like. And you become very unpopular yourself. And so Netanyahu himself is probably more popular than his coalition partners, but he can’t govern without them and they drag him down.

Sarah [00:33:16] I have some stress about the number of Israelis leaving Israel and particularly like how big that number is. Would that ultimately empower the Ultra-Orthodox? Listen, I’m an American in Kentucky and this is probably not what I should be worrying about. But because the numbers are pretty high of people leaving the country, what do you think about that?

Yair Rosenberg [00:33:40] When I last looked at this, you do have a certain amount of outflow but you also have inflow. You have people come and move to the country from around the world sadly because you have rising antisemitism in a lot of places around the word that spurs people to move to Israel. So you have this give-and-go push to take of course while the wars were going on people left because if you had the means and you didn’t want to be in a country that’s getting cruise missiles by Iran or something, you could if you wanted to. Some of those people are coming back. I think the more that this far-right coalition runs Israel, the more people who are more secular and liberal will say I don’t want to be here while this is going on. We had some level of that phenomenon sometimes in the United States where some people might move to Canada or whatever. But as you know it’s a certain percentage but it’s not a huge and so that has been going on. I do think if say for example somehow Netanyahu did win another election and just kept doing what he’s doing, you start to see more of an outflow and what we could say more of a brain drain because many of these people are associated with liberal and academic and artistic circles. And those people can go somewhere else where they can do those things without living under a particular regime, but also a regime that interferes with them. Because one of the things that the hard right government has been doing, for example, is going to war with Israel’s higher education system if this sounds familiar.

Sarah [00:34:54] It really does.

Yair Rosenberg [00:34:55] They see it as a hotbed of dissent. As sort of a place where there’s more pro-Palestinian sentiment. To give one example, I don’t think this ever really makes any news or headlines in the United States, but one of the things that Israeli academia succeeded in doing is building very successful affirmative action programs for Arab students in Israel. And the way they did that is not through like admissions policies where they would accept more people from this or that community because the concern is if you let people in just through a policy that gives them an extra advantage in admissions, they then go to school and then it turns out they don’t have the skills to succeed and they don’t get the degree and what did you actually accomplish? And so what they did instead is they go and they identify high performing students from minority communities in Israel like the Arab community and then they put them in preparatory programs which fill in the skills that they’re missing from their disadvantaged backgrounds and schools and so then by the time they take the admissions tests and they get to college they’re way up right up to speed. And so they didn’t just achieve proportional Arab enrollment in admissions, but also in graduation which is the real goal. And this sounds to you and me like a success story, but to people in Netanyahu’s coalition, this is a real problem because they don’t want to be integrating Arabs. They don’t want to have them as part of the Israeli polity in public.

[00:36:10] If they really had their way, some of these people I think would try to expel them. And so you had, like, Bezalel Smotrich, who’s currently a minister in Netanya’s government, but years before, when he was just a backbencher with no power, he gave a speech basically saying that all of these Arabs are stealing, they’re faking their scores or they’re stealing spots in universities from good, rock-ribbed Israelis. And this led to a big backlash, so presidents denounced it, people started posting, Arab students around the country started posting their equivalent of the SAT scores, it’s called the spectrometry, became a whole viral thing. But now Smotrich is in the government and one of the things that he’s been trying to do is to starve these academic institutions of the funding they use to run these affirmative action preparatory programs. And then what’s wild to me as someone who covers this is, of course, if you come to say American academic leftist circles, they spend a lot of their time trying to boycott the Israeli universities who are being attacked by Bezalel Smotrich because they’re trying to achieve proportional Arab enrollment. And this to me is a good example of Israel as the sort of weird symbol that you said rather than the actual country and how it works. Once you understand how it work, you say that’s insane. Why are you doing that?

[00:37:16] Another example of this government sort of going after the liberal, cultural, intellectual sphere is the culture minister people have been going after Israel’s filmmaking community. A lot of Israel’s film making community gets some level of government funding. This happens in many countries where you don’t have as big a film industry. And so you get funding for the arts, which we have also and the Trump administration has been hacking away as well. But for example in this year’s Oscars, the film that won Israel’s Oscars, the Ophir Awards, was a film that was extremely critical of Israel treatment of the Palestinians and portrays the experience of Palestinians under Israeli occupation. And that’s the film that won the Ophira Awards. And in response, the government is saying we’re going to just cut off all this funding and we’re going to punish these people. And once again, if you go into cultural circles internationally, when they’re talking about it, they’re like we should boycott the Israeli film industry because they get funding from the government. And so that’s technically true, but they’re misunderstanding what is happening, which is they take the funding for the government then do things that this government doesn’t like, and they’re actually getting attacked by the government for it. So again, I understand why people are not aware of all of these sorts of details, but it leads to people sometimes with good intentions making very bad decisions.

Beth [00:38:27] It’s so helpful to hear that and important. We’re hearing from listeners who are all over the world right now, who are saying that the people they live around are horrified that Americans are in mass, in the streets all day, every day, protesting the Trump administration. Because what you see from afar in a country is never the entire story of what’s happening in that country and how everyone feels. So I know you need to run, but as a wrap-up question, I just want to ask you, I comfort myself when I get stressed about the news by saying this is an election year, like there is something to do, there is that can make a difference. I wonder how crucial this election year feels to you in Israel, how much of an opportunity you think there is to change the status quo and to change the way the world is talking about Israel as that caricature instead of a diverse country full of people with different opinions and objectives.

Yair Rosenberg [00:39:20] It’s very hard to game out how people will react or change their minds about things. But as a reporter looking at this election, I think, yeah, it’s incredibly consequential for the future of Israeli society. This current government is one that has gone after various democratic foundations of Israel’s constitutional order, so to speak. It’s one that has vastly expanded their settlement footprint and their policies towards Palestinians in the West Bank. Obviously, it’s one that chose to prosecute the Gaza war in the way that it has. And Israelis have different opinions on all these things, and some of the people who agree with some of these policies would vote for the opposition. But there’s a huge proportion of the country, many millions of people who are currently not represented in leadership, and they would be. Their parties, their leaders, their people would certainly be sitting at the table and making decisions. This current Israeli government is not particularly interested in being part of a broader sort of Western family of nations. They’ll do it and they’ll take the advantage of it when they can. But if it asks them to do anything or to sacrifice anything, they’re unlikely to do it. Whereas, many of the people who might win in the next election, including some people who are right-wing in orientation, do care about international standards and being part of European Union agreements and international alliances and things like that. And that imposes, they understand, certain obligations. And so a lot of those things hang in the balance on this kind of election. It’s going to be viciously fought. I think something that hasn’t really gotten attention, but perhaps I’ll write about it. Others might. Not unlike in our country, Netanyahu, if he sees his hold on power slipping away, might try to delegitimize an election result. He actually did it in the last election, and then he ended up winning, so he stopped talking about it, which is very interesting. It’s like you’re an alleged fraud, and then you win, and so you’re like, oh, well, now you’re in charge. I’m sure you’re going to run a bunch of--

Sarah [00:41:05] Again, it sounds familiar to me.

Yair Rosenberg [00:41:08] And so and in this case I think he actually learned it from Trump. Some of these things he saw was successful for Trump and he thought maybe I actually could get away with that. And so it’s an incredibly pivotal point for just will Israel’s democratic process work properly, right? And then what sort of orientation you might have towards the world? It’s hard to know exactly every detail or how these things would go, but it matters a lot. And I think that that’s a wonderful thing about democracy, is that the elections can actually matter and that people have these sorts of options and choices. And we are fortunate to live in the United States of America where that is still true. And Israelis are fortunate when they get to vote that they get do that too. And so we’ll perhaps come back here for a conversation when they get closer to making that choice.

Sarah [00:41:51] I hope so. Thank you so much for coming on Pantsuit Politics.

Yair Rosenberg [00:42:04] Thanks for having me.

Sarah [00:42:04] Okay, Beth, what was the middle name you were born with first?

Beth [00:42:08] Ann.

Sarah [00:42:10] Beth Ann Thurman.

Beth [00:42:11] Beth Ann Thurman, yep. Not Elizabeth, just Beth and Ann. And most of my family calls me Beth Ann.

Sarah [00:42:21] You went by Beth Ann in college, too.

Beth [00:42:24] I’ve gone by Beth Ann on and off over the years.

Sarah [00:42:27] Does N have an E?

Beth [00:42:30] No. It’s about as straightforward as you can get. Like my parents are real down to earth people and you can tell in my name.

Sarah [00:42:36] How do you feel about Beth Ann?

Beth [00:42:38] I like Beth Ann. Actually, there are times that I wish I had just stuck with it. It’s hard now to make a pivot back, but there are people in my life who call me Beth Ann, even people who are newer to me. And there are people, I think, if you love me in a very particular way, it sounds right to me to hear you say Beth Ann. And then there are other people who will use it that I’m like you’re not a Beth Ann person to me. So I’m kind of weird about it. What about you?

Sarah [00:43:02] I was born, small Kentucky town, 1981 as Sarah Lyn Stewart. One N.

Beth [00:43:14] One N? L-Y-N.

Sarah [00:43:19] Yes. I said, why? I don’t know. My mother is not a strong speller. It’s not her strong slate. So I don’t know if it’s just like a misspelling. She doesn’t know, but it was annoying. I don’t mind Lyn. Lyn is my mother-in-law’s name. But the L-Y-N? Come on, what are we doing?

Beth [00:43:42] Would you have preferred two N’s or two Ns and an E?

Sarah [00:43:45] Ew, no, I don’t like the E. Just two Ns.

Beth [00:43:47] Just the two Ns. Okay.

Sarah [00:43:48] An E is a little superfluous in my opinion.

Beth [00:43:52] Yeah.

Sarah [00:43:52] Okay, so what’s your middle name now?

Beth [00:43:54] It’s still Ann. I just took Chad’s last name. Beth Ann Silvers is my name.

Sarah [00:43:57] I think this is a shocking choice.

Beth [00:44:00] Do you?

Sarah [00:44:01] I do. Most people, including me, don’t they drop their middle name and take the maiden name as the middle name?

Beth [00:44:10] I don’t know. Never occurred to me to do it.

Sarah [00:44:12] It didn’t even occur to you?

Beth [00:44:14] No. Well, I think part of it is because Beth Ann is my name to so many people.

Sarah [00:44:19] I mean, I never went by Sarah Lyn-- I mean that’s not true. Some people call me Sarah Lyn, obviously my family, but it’s pretty rare.

Beth [00:44:25] Yeah, I don’t know a way through life without being Beth Ann.

Sarah [00:44:28] Well, clearly, you were not a women’s studies minor.

Beth [00:44:33] No I was not.

Sarah [00:44:33] I’m just saying because the last name was a struggle. So there was no way in hell I was not only going to change my last name, but drop it completely. Even though I don’t like Stewart, it’s not a fun last name to have. Although it was a beautiful, alliterative name. Sarah Stewart is nice. There are other Sarah Stewart’s out there. Not related to our middle names at all. I was going through this old scrapbook and I found this clip I took from People Magazine, where someone had written in as Sarah Stewart, which I guess is why they clipped it, or why I clipped out. Okay, I guess just seeing my name in People Magazine. Except it was S-A-R-A. Anyway, it was about this woman criticizing Cindy Crawford and Randy Gerber for having a home birth and how dangerous that was, and even a midwife isn’t properly prepared. Is that not hilarious considering I went on to have home births?

Beth [00:45:31] That is funny.

Sarah [00:45:33] But, so I liked the name Sarah Stewart. I didn’t like Stewart because people call you Stu. So it’s not like a deep affinity for Stewart. But what I always said at the time, I told Nicholas, I was like, I don’t mind changing my name. I do not like that I am the only one changing my names. That part bugs me. I put in a hard press to make a new name, which one of our college professors did, which was Hart, the H from Holland and the A-R-T from Stewart. And I thought it was a strong suggestion that he rejected out of hand.

Beth [00:46:05] Yeah, it’s a great choice.

Sarah [00:46:05] I didn’t know what I was going to do until my rehearsal dinner. And now this middle name has morphed into a discussion of changing my name. But either way, that’s why there was absolutely no way I was just going to drop my last name altogether.

Beth [00:46:20] It didn’t bother me and I honestly think if I had talked with my parents about it, I think it would have been harder for them for me to drop the Ann the middle name.

Sarah [00:46:30] Is it a family name?

Beth [00:46:32] No, actually the story is that I was going to be named Teresa. That was the name they picked for me. And then I was born and my dad looked at me and said, “She does not look like a Teresa. She looks like a Beth Ann.” A name they had never considered in whole or in part, no discussion whatsoever. He just looked at me and dubbed me Beth Ann. And I think it would have been totally bizarre for them if I had lost the Ann along the way.

Sarah [00:47:00] That is so interesting. I didn’t want to hyphenate because I’m lazy and I don’t want to spell that out every time. So I dropped the L-Y-N. Made Stewart. And honestly, I really wish that I had named-- wish that I’d hyphenated, but Griffin’s name is Griffin Stewart Holland, and I really wish I’d named all three boys just Stewart Holland, Stewart as they’re middle name.

Beth [00:47:24] With the creation of the new last name, I know you have a real affinity for genealogy.

Sarah [00:47:29] That’s why I didn’t do it. And that’s ultimately why I changed my name. Honestly. Because I thought like, okay, there has to be a process through which we can trace and connect to each other. And I don’t love this, but this is the way that we have been doing this for hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of years. And like blowing it up over like my individual concerns. Look, I had a thing against you do you [inaudible]. No, that is ultimately why I didn’t do it. And that’s why my kids all share my husband’s last name and my last name obviously. Well, because that’s the other thing. I was, like, no, I’m not going to keep my name and none of my kids are not going to have my last name. Hell no. I made them. So yeah, obviously, also fun fact, I picked every single one. I named my children. I said, you picked their last name boy. You made a choice. You picked their name, so I will be picking their first names. So I named all of my children.

Beth [00:48:26] Well, I made a Post-it note of possible names and said to Chad, “I would love for you to subtract, but not add.” That’s how I went about it. Like this is the list. What do you like on this list?

Sarah [00:48:38] That’s a nice compromise.

Beth [00:48:39] And then we went back to that list because we had two girls. We just went back to that same list when I was pregnant again. And Chad was very agreeable about that process. I think it might’ve been different if we’d had a boy, but he was very agreeable about that process for girls.

Sarah [00:48:53] Is he like a second or a third or anything?

Beth [00:48:55] No, his middle name is his dad’s middle name. So I think that that probably would have been an expectation. But no, he was agreeable about it. With the changing of my last name, I really just thought about like Christmas cards and school stuff and just felt like, as much as I do embrace you do you, in a lot of ways, I just felt like I don’t need to make a decision about this. Like, I’m just going to do the thing that we do. And it’s worked out fine, except that it is very hard to have a plural last name. So many people will write my name is Beth Silver without the S. And then you can tell that people really struggle with the Christmas cards. Like, are we the Silvers’s or like the Silvers with an apostrophe or whatever.

Sarah [00:49:36] I struggle when the wife and the husband have two last names. I’m just going to be honest; I don’t Know how to put that on a Christmas card. Usually I just do like the blank and blank family. It’s rough. It is a tough call as much as deciding how to address Christmas cards is tough. I was standing up at my rehearsal dinner and my uncle was like so what should I say at the end? And honestly, whatever my decision was or would have been, I can’t stand Mr. And Mrs. Nicholas Holland. Please erase me completely from the picture. Just love that so much. And people were literally like yelling it’s an honor, you should just do it. Like yelling from the audience at my rehearsal dinner. And Nicholas goes, “Just say Sarah and Nicholas.” Just announce this is Sarah and Nicholas.

Beth [00:50:26] Oh, that’s funny.

Sarah [00:50:28] I believe I took a vote among my bridesmaids in the car on the way to dinner.

Beth [00:50:37] Amazing. It’s just such a hard one because you really want to respect other people’s choices. That’s how I feel with the card addressing and that kind of thing.

Sarah [00:50:43] Yeah, I don’t want to hurt anybody’s feelings.

Beth [00:50:45] I know that it’s much more important to some people than it is to me, and I want to honor whatever choice they’ve made. And, for me, I guess this is a very Enneagram two thing to do. I just thought this is the easiest for everybody. That’s fine. Fine with me.

Sarah [00:51:00] Yeah, and sometimes I’ll just be like I’m just going to address it because a lot of times it’s like my friends from law school and it’s like the woman is who I’m the friend with, so I’m going to address the card to her. I doubt the husband will even see it. You know what I mean? She’s going to want to hang it up [inaudible] on the outside. If I have offended you over the course of my 23 years sending Christmas cards, I apologize.

Beth [00:51:22] Never our intention to offend.

Sarah [00:51:24] Sometimes, but not with the Christmas cards. Just saying. Well, thank you for joining us in this conversation about middle names that apparently wasn’t about middle name at all. Again, huge, huge thank you to Yair for joining us. It is always such a pleasure to have him on the show. We will be back with another new episode on Friday and until then, keep it nuanced, y’all.

Show Credits

Pantsuit Politics is hosted by Sarah Stewart Holland and Beth Silvers. The show is produced by Studio D Podcast Production. Alise Napp is our Managing Director and Maggie Penton is our Director of Community Engagement.

Our theme music was composed by Xander Singh with inspiration from original work by Dante Lima.

Our show is listener-supported. The community of paid subscribers here on Substack makes everything we do possible. Special thanks to our Executive Producers, some of whose names you hear at the end of each show. To join our community of supporters, become a paid subscriber here on Substack.

To search past episodes of the main show or our premium content, check out our content archive.

This podcast and every episode of it are wholly owned by Pantsuit Politics LLC and are protected by US and international copyright, trademark, and other intellectual property laws. We hope you'll listen to it, love it, and share it with other people, but not with large language models or machines and not for commercial purposes. Thanks for keeping it nuanced with us.

He mentions this as a strategy for combatting antisemtism and other forms of prejudice in today’s episode.

At the 9 min mark there’s an audio error that has a very pronounced over recording of ( I think) Beth saying “shit” and it gave me the biggest laugh and I listened to it multiple times, just FYI. (On Spotify)

In the early 1980s there was a teacher at my junior high who had chosen her grandmother's first name as her last name. She was very open at school about her disdain for the practice of labelling daughters as belonging to a father or a husband (she was divorced with two daughters, who were my friends). That has always stuck with me, as a feminist and daughter of divorced parents and grandparents (I had 5 parents by the time the marriage-go-round stopped spinning. Last names were not a trivial matter.)

I chose my husband's last name because I have great respect for his dad and family, something I didn't have for my own father so it didn't make much sense to keep my maiden name. If I had never married, I probably would've changed my name like that teacher did, but my maternal grandfather was the only grandparent who supported or even acknowledged me, so I considered taking his last name.

As for my middle name, I never used it or even really connected to it, but I like the Z in Suzanne. My maiden name starts with a Z and I always liked my initials, so I kept that letter and dropped everything else. That vestigial letter as my middle name has caused some minor problems - had to send back my grad school diploma and explain (again) that the Z is not an initial - but I'm glad I kept it. It honors my father's name and my mother's choice of middle name without placing either of them on a pedestal they don't deserve.

This name conversation brought up some heavy stuff for me, which is ridiculous given the very heavy topic of Israel at the heart of the episode. My parents divorced soon after I was born, and I was brought up with my stepfather's last name - much against my father's wishes. When I was young, my mother once made a point of telling me that she gave me the middle name Suzanne so that I'd have lots of choices - I could go by Sue or Anne or SueAnn or Susan (why not by the French-sounding Suzanne? Idk). But neither she nor anyone else I knew, family or friends, had ever called me by any version of my middle name. Her thoughtfulness around the name seemed pointless. Years later, when I was in my forties and long after my father had died, she started telling people - in my presence - that Yvette was the name of one of my father's mistresses and that's why he gave me that name. I mean...who does this?! Not only had I never heard such a thing before, but why say such a thing around other people?! It's painful enough to hear it by myself. And why, if she hated my name so much, did she not just call me Suzanne throughout my childhood? She could enroll me in school under my stepfather's name but not under my middle name? At least my middle name was my actual legal name!

My father always told me he named me Yvette after the French American actress Yvette Mimieux - I always joke that she was French, petite and blonde and I am none of those things. This unusual but somewhat glamorous name is the best gift he ever gave me; I wouldn't be who I am today without it. I don't understand why my mother didn't take it from me when she could have, but she certainly doesn't get to take it now.

Oof. Thanks for the space to get that out. We all have such complicated things to say about something as seemingly simple as names, I can only imagine how complicated it is to be Israeli with all the contradictions in that country. Thank you for an episode that helps us unpack and grapple with all that.